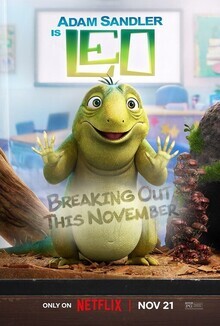

Adam Sandler does That Voice again in the animated movie “Leo,” when bringing a slight personality to a 74-year-old class lizard. It’s that gurgly, raw monster baritone that he’s been doing for years, the one that probably invented phrases like “Shibbbittty bobbity dooo!” and made for big laughs on “Saturday Night Live”’s Weekend Update. Sandler does the voice again, gentler but with more congestion, in a vehicle that should be fun—voicing an old lizard who covertly imparts perfect life advice to quirky fifth-graders. And yet the Sandman’s modern lazy artistic side takes over, fully flexed in this Netflix project rife with stiff animation and awkward gags. Even the spare musical numbers with Sandler doing That Voice are underwhelming.

“Leo” has self-awareness with a slight adult edge from the beginning, so it gets the reference to E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web out in the open early. It’s the book the students will have to read, which they groan about while fearing their curmudgeonly substitute, Ms. Malkin (voiced by Cecily Strong). But therapy is larger on the minds for this story, and each time 74-year-old lizard Leo goes home with one of the students for the weekend, he both reveals that he can talk and also that he knows what each child needs to hear. One girl is losing out on friends and connection because she talks too much; a sheltered boy (who is even followed around by a dutiful drone) learns to climb walls and dangle over the side; a snotty girl realizes that while her father (Jason Alexander) has success as Dr. Skin, it doesn’t mean she’s better than her classmates; a lovable lunkheaded boy says he doesn’t know where babies come from.

Right, the whole talking lizard thing. The original script by Sandler, Robert Smigel, and Paul Sado is incredibly pat and treats this element as a poorly kept secret. Sandler’s scaly shrink asks each kid not to tell anyone else, to preserve how what he is telling them is special. In one of this overlong movie’s conflicts, everyone eventually realizes that the class’ favorite lizard is beloved for that exact reason. But it’s not magical that Leo speaks, and it’s not as big of a deal as the secrecy warrants; it’s just the script trying to give Sandler a chance to be a cute, wise animal. What more do you want, “Leo” asks. There’s also a turtle named Squirtle, voiced by Bill Burr, who antagonizes Leo and his therapy pursuits and is generally the source of the story’s offhand urination jokes.

This babysitter of a movie is, at times, inexplicably, a musical. Not in a grandiose uniform sense. But in some of its sequences about Leo’s impact on the young ones, there is some singing before directors Robert Smigel (who wrote the songs), Robert Marianetti, and David Wachtenheim shuffle on. Emphasis on some, as the musical numbers are cheap, whether it’s their short length, their spare piano and light strings arrangement, or the lack of choreography. “Leo” hopes to compete with other animated movies that are soundtracks first and stories second, but the cut corners are too obvious.